Tucked away in the southern corner of Taiwan, the remote island of LanYu, or as it’s more popularly known, Orchid Island, is all but hidden. Tourists flock to this idyllic destination for its stunning coral reefs and dense forests covered with the flower that gives the island its unique name. Among the shimmering fish and calm sea breeze there is a less picturesque threat lying beneath what appears to be LanYu’s pristine surface. Today, there are nearly 100,000 barrels of radioactive nuclear waste polluting the island.

In the early 1970s, Taiwan began developing its nuclear program, producing mid- and low-level nuclear waste. Taiwan’s Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) decided to store its radioactive waste on the Long Men area at the southern tip of LanYu in 1974 — resulting in the beginning of a 30-year battle against the Island’s Indigenous peoples.

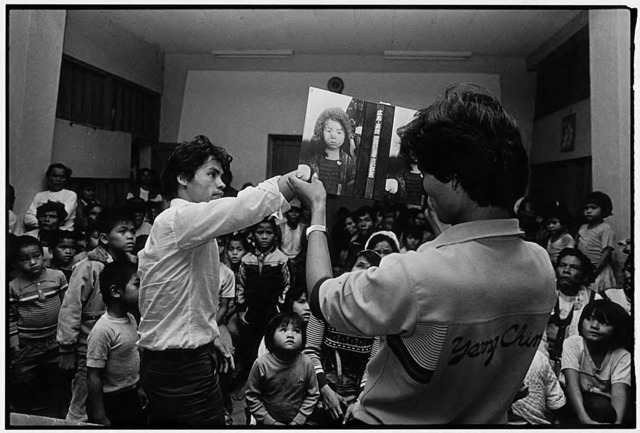

Guan Xiao-rong, Educated young native Yami men show to villagers and children the aftermath of 1945’s nuclear bombing of Japan, © Guan Xiao-rong, courtesy the artist & University of Michigan

With a population of less than 3,000, the Tao people have inhabited LanYu for thousands of years. The Tao are renowned for their peaceful lifestyle and a religious reverence to nature. To the Tao, the island is not only sacred to their culture, but is also tied to their livelihoods. LanYu’s geographic position suits the Tao’s sea-faring nature and allows them to remain self-sufficient. Their shared love for community and cooperation has established no need for an official government or modern jails.

In a true historic fashion, this vulnerable population has become another unwilling victim of exploitative politics. From the very beginning, the Tao were manipulated. The AEC first approached the Tao district commissioner, who at the time was illiterate, with a contract to build a fish cannery. Conveniently, they omitted any mention of a nuclear dumpsite from their dealings. Sadly, the deception did not end there. It was agreed that Orchid Island would be a temporary storage site, and the radioactive waste was to be removed by 2002. Unsurprisingly, that deadline came and went, and the waste still remains today.

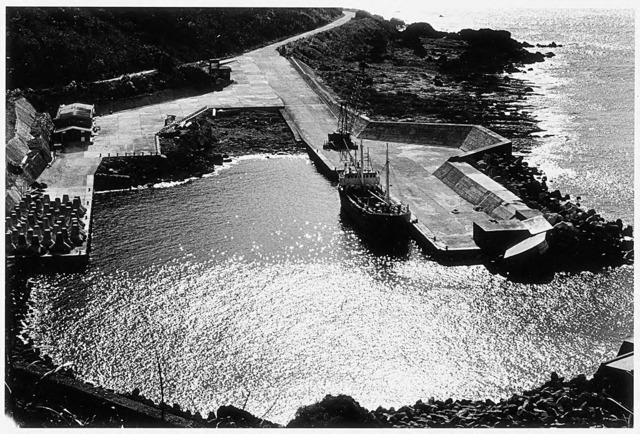

The dumpsite’s original structure was not created with the intention of safely storing nuclear waste. Currently, it circulates water through a designated pool, resulting in absorption of radiation before releasing the water back out to sea. This pool, however, did not exist for the first eight years of the dumpsite’s existence. And in the first eight months after it was added, radioactive material was already poisoning the pool’s soil. We must ask ourselves, how much radioactive material contaminated the Long Men’s waters before the pool existed?

Guan Xiao-rong, The pier where nuclear waste shipped from Taiwan is unloaded, © Guan Xiao-rong, courtesy the artist & University of Michigan

The island’s location poses another terrifying threat. Each year, LanYu is slammed with seasonal typhoons that can produce up to a foot of rain everyday and record wind speed. The island is also on an active faultline which caused an earthquake during the dumpsite’s construction. These natural disasters compromise not only the structural stability of the dumpsite, but also the security of the nuclear waste.

The AEC’s disregard for the health, safety, and wellness of LanYu and its inhabitants reinforces the unspoken norm that the Tao are expendable. Chen Chien-nien, the Minister for Indigenous Peoples, admitted that they were targeted as Indigenous peoples: ”If the residents were Chinese or Taiwanese in the beginning, they probably would not have built the dump there.” Nuclear waste can linger in land and water, meaning that the Tao can no longer fish in Long Men’s waters. The government’s apathy has placed the Tao people in peril. The creation of the dumpsite has severed their sacred ties with nature, endangering their culture.

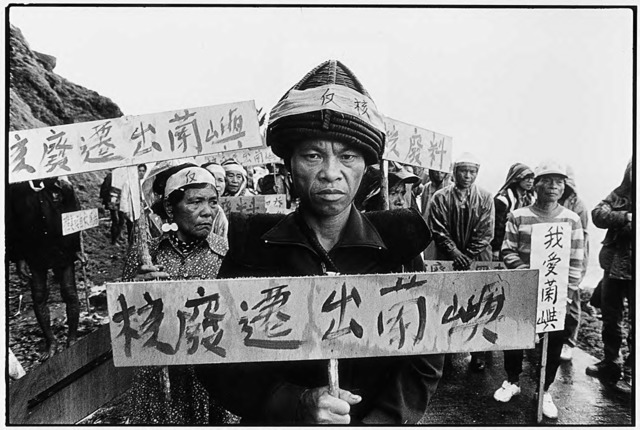

The Tao initiated an anti-nuclear movement with their first protest in 1988. Three years later, the Tao coordinated simultaneous protests in LanYu and Taipei and delivered their demands directly to the Taiwan Power Company. In 2002, their sit-in of nearly 2000 people at the dumpsite sent a striking message of outrage and resilience to the world. One decade later, the Tao wore their traditional dress, clenched their fists in defiance and performed their ritual to drive away evil spirits from Long Men.

The Tao’s protests highlight their exceptional strength as a community. However, the plight of the Tao people can no longer be theirs alone. Historically, the nuclear system has disproportionately victimized Indigenous peoples worldwide. It is an ongoing and undeclared nuclear war against their cultures, poisoning their communities and silencing their protests. The Australian Aboriginal peoples, the Marshallese, and the Navajo Nation are sadly just a few of many suffering a similar legacy. They are outnumbered, oppressed and forgotten: victims of a corrupt system.

Guan Xiao-rong, Local demonstrators hold signposts that say “Nuclear waste out of Lanyu”, © Guan Xiao-rong, courtesy the artist & University of Michigan

But the twenty-first century arms us with an even stronger weapon. Intersectional activism is the only way we can remedy the consequences of these political inequalities. The most privileged individuals must actively listen to those systematically oppressed, and use our platforms to amplify their voices. Rewriting the framework of equality to prioritize Indigenous struggles is vital in the fight for true justice.

We must listen to and learn from the Tao culture: strength stems from the community. Now, Beyond the Bomb needs your help. The threat of nuclear weapons is a global issue, but the fight begins at home. Tell your representatives to amend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to include the unwilling victims of nuclear testing in New Mexico.